Accessible Technology at the Library

May 19, 2025

Because access to technology is a necessary part of our lives, we all benefit when technology disability inclusion is a priority. We can compare the benefits of accessibility with the "curb cut effect." This means that sidewalk ramps benefit people who use wheelchairs (the intended audience). They also benefit bicyclists, parents with strollers, and people making deliveries using dollies. Accessibility may first bring to mind physical accommodations like larger restroom stalls or easier-to-navigate parking. However, equitable and accessible elements in technology are as important.

This year, the United States celebrates the 35th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This law has led to improved conditions for people with disabilities. But the ADA didn’t originally include digital accessibility, and legal cases involving technology changes move slowly. The first major case to allege inaccessibility online as a violation of the ADA was in 2002, where the U.S. District Court ruled that Southwest Airlines' website did not need to be a “place of public accommodation” as stipulated by the ADA. A 2019 case (involving a blind man being unable to order pizza) was a step forward for website accessibility rights. And in November 2024 alone, there were 363 ADA lawsuits regarding digital accessibility.

A 2021 article in Assistive Technology noted that digital accessibility is always evolving:

“Although the rate and quality of technological change has become a tired cliche, these factors remain central to the challenge of achieving and sustaining digital accessibility for persons with disabilities.... In fact, it is perhaps best to understand digital accessibility not as a state, but as a constantly changing interactive process.”

Major tech companies have made many achievements in this realm. Inclusive design—often called universal design—is becoming the standard. While accommodations should be made available no matter what, and designs for disabled users shouldn’t have to benefit everyone, the hope is that the curb cut effect will make inclusive design an obvious best practice. The following accessibility features, now commonplace, are just a few examples of digital inclusion benefiting everyone.

Closed Captioning

In 1980, after many experiments and trial and error, closed captioning for a pre-recorded television program was available for the first time. However, it required a $250 decoder box from Sears. It wasn’t until the Telecommunications Act of 1996 that closed captioning was required for major broadcast networks. In 2010, the Twenty-First Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act addressed captioning for videos redistributed on the internet and what we now think of as streaming.

Today, this function is a necessity for many, not just for people with hearing-related disabilities. A recent survey of Americans found that 70% of Gen Z respondents (current teens–late 20s) use captions most of the time. Closed captioning can make it easier to:

- Learn a language

- Understand actors speaking with accents

- Understand dialog that's too fast or too quiet

- Focus on what is being shown

All videos on our website and YouTube channel provide captions. If you’re ever in a loud environment but want to learn how to use a Cricut vinyl cutter, you still can!

Screen Readers

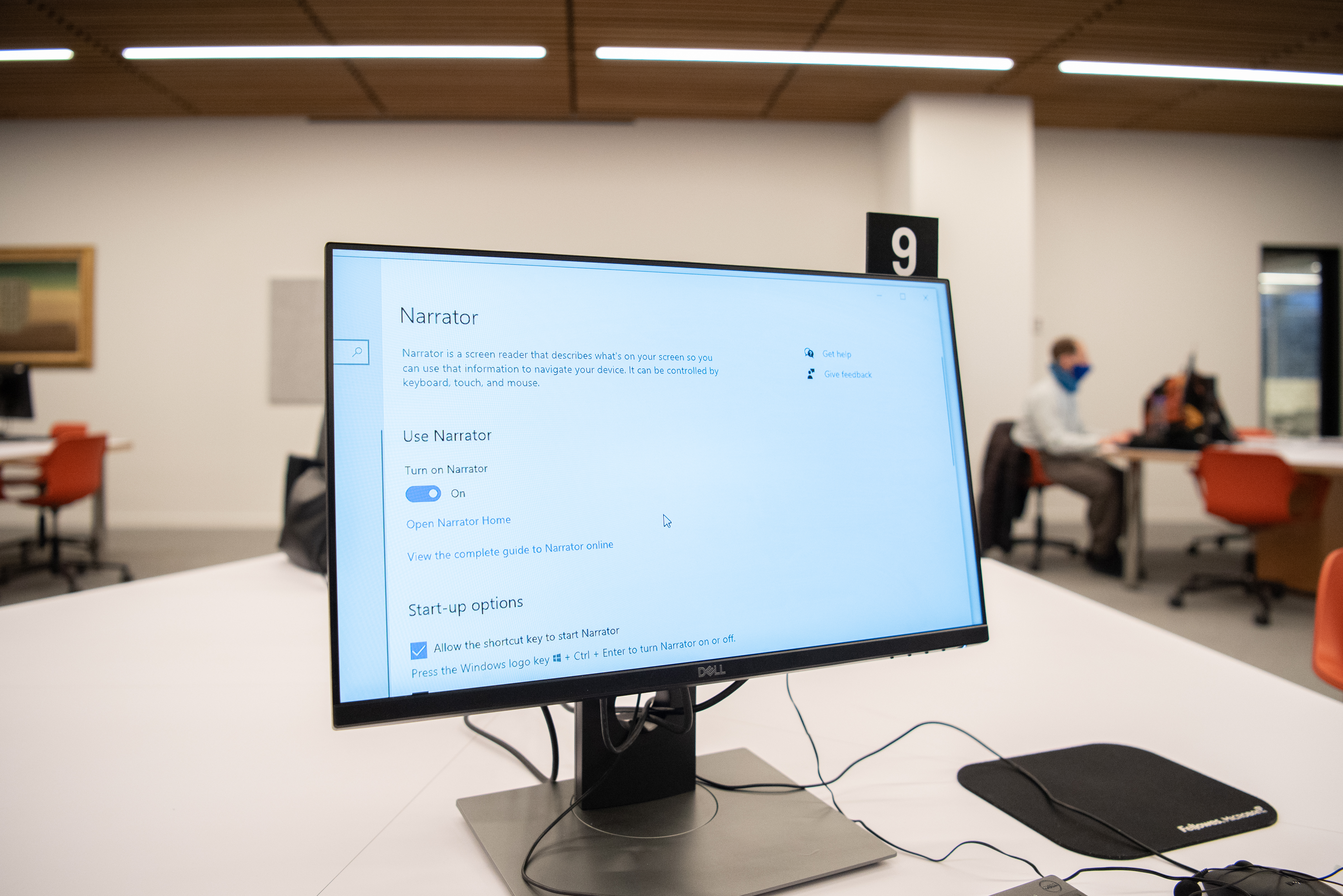

A screen reader is adaptive software that lets people hear text on a computer screen rather than see it. Settings can allow content to be auto-read when users load a page or users can select parts of a webpage. IBM Screen Reader was one of the first, developed to make computers accessible to IBM’s blind staff. Job Access with Speech (JAWS) was created in 1987 and later integrated into Microsoft Windows. JAWS is still popular and is a high standard for screen readers, second only to NVDA–NonVisual Desktop Access. In the Verge’s article, “The Hidden History of Screen Readers,” it’s noted that “The NVDA community is enthusiastic, even passionate about the software. Discussions comparing one screen reader to another—very much like the iPhone vs. Android or Chrome vs. Firefox debates—can become religious.” People are passionate about this technology because of the access it provides to digital content.

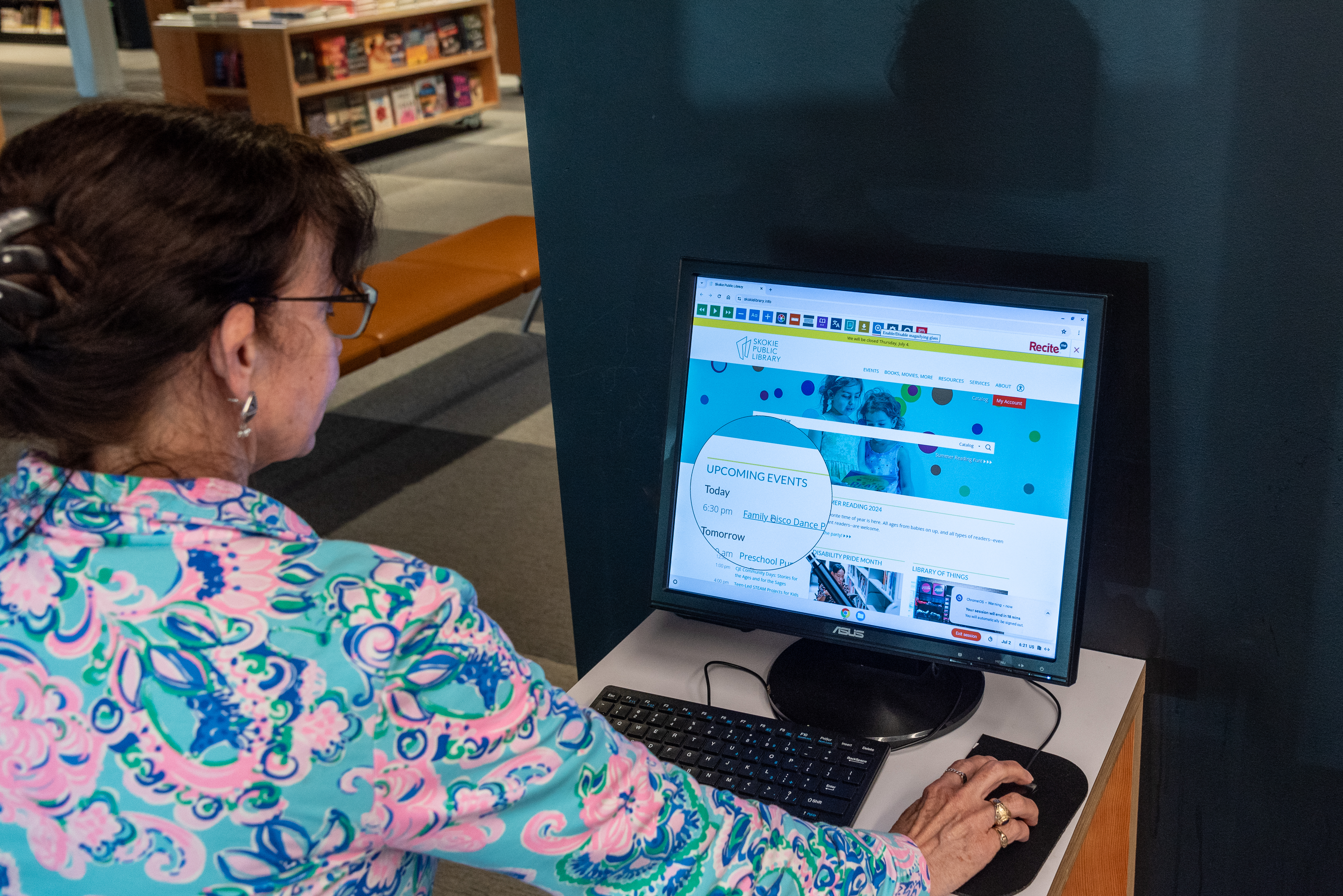

While visually impaired and blind users are the most obvious beneficiaries of screen-reading software, it also benefits people with learning disabilities like dyslexia and people who are illiterate. Many people who prefer audio-based learning can also benefit from this assistive technology. All public computers on the library's second floor are equipped with NVDA software, and we provide ReciteMe on our website. This tool provides screen-reading options and many more features for using the website.

Accessible Websites

While the ADA did not initially address digital “spaces” because it was enacted before internet use was widespread, other governing bodies stepped up to create guidelines and best practices. Specifically , the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) has created a series of standards, known as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). WCAG is technical, primarily intended for web content and tool developers. It provides four main guidelines that are invaluable when considering basic inclusivity and accessibility across technology as a whole:

1. Perceivable: Information must be presentable to users in ways they can perceive. This includes providing text alternatives for images and captions or audio options for multimedia. It also includes simply presenting content in more than one way. “Perceivable” stipulates specifics about font size, color, and contrast, because not all fonts are equally readable.

2. Operable: This means that websites cannot require interactions that a user cannot perform. One way this is often implemented is with keyboard functionality so that a mouse is not required. Website navigation is a big aspect of accessibility, with menu options sometimes inadvertently creating barriers.

3. Understandable: Understandable websites not only have information presented clearly, but they also make things easy to find and use. Appropriate wording can be used, as well as summaries, instructions, and guides.

4. Robust: Content must be able to be used and interpreted reliably by different users, including assistive technologies. As technology continues to evolve, websites must remain accessible and able to be interpreted. As we saw with closed captioning, there can be many different versions of similar assistive technology, and "robust" websites need to be able to work with a variety of tools.

These four guidelines, spelling POUR, outline understanding how to make digital environments more inclusive for people with disabilities. They also make things more user-friendly for us all. Basic computer navigation is improved by making buttons and labels clear, and getting things done is simpler when things are easy to read, with appropriate and consistent colors and fonts.

Why are digital inclusion and accessible technology important at the library?

According to Pew Research from 2021, 81% of adults without disabilities own computers, compared to only 62% of adults with disabilities—a gap of 19%. In a world where virtual spaces complement or even replace places like offices, classrooms, and public service providers, technology access for people with disabilities must not be an afterthought. “Ultimately, the objective is for persons with disabilities to enjoy access equivalent to that which is afforded to all other citizens, without being forced to wait for years.”

The library continues to prioritize inclusive and accessible resources and services. Everyone is welcome here. That welcome includes ensuring access to technology and all it offers.