Treaties and Native Land in Illinois

February 21, 2025

Skokie Public Library is on the ancestral homeland and trading ground of many First Nations people and tribes. They are the Council of Three Fires (the Ojibwe, the Potawatomi, and the Odawa), and others, including the Menominee, the Ho-Chunk, the Miami, and the Sauk. The Great Lakes were—and are—a place to gather and exchange ideas.

Many Indigenous Americans still live in the Chicago area. However, throughout the last 200 years, American colonizers and the United States government acted to force the original residents out. Our last blog post about local Native history took a general look at this past. Here we look at how the federal government used treaties to claim this area.

Predatory Treaty Practices and the 1833 Treaty of Chicago

In his 1828 presidential election campaign, Andrew Jackson promised to remove all Native tribes to land west of the Mississippi River. After his victory and inauguration, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830. This act kicked off a series of land treaties over the following decades. In middle school, Skokie public school students learn about the forced displacement in the southeast known as the Trail of Tears. That was only one such action. By September 1833, negotiators came to Chicago intending to expel all Native tribes from the valuable land in the Great Lakes region.

Settlers colonizing the area had made frequent reports that Indians had mistreated them. These reports pressured the federal government to act. Local officials thought most of the reports were false. Officials believed the settlers just wanted access to more land, but newspapers covered the stories and ensured they were widely seen.

Many historians believe the government’s primary motivation for acquiring land in the area was more about money than protecting settlers. After the War of 1812, the United States was broke, and land treaties with Native Americans had become a key source of money. The government acquired tribal land at a fraction of its real value and then sold it to speculators, reaping the profits.

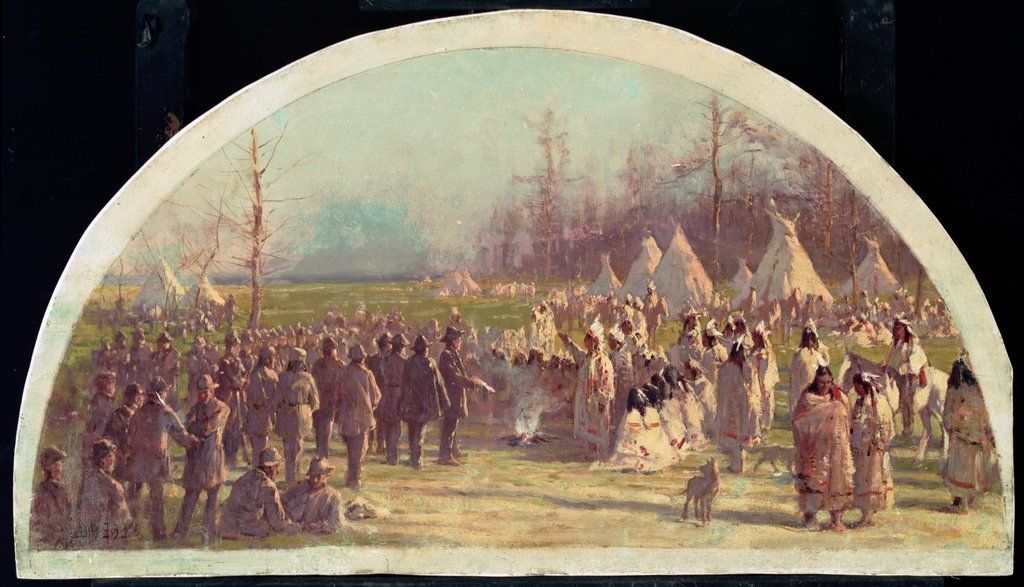

These financial benefits encouraged government agents and other parties to use underhanded tactics to secure favorable terms. At the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, whiskey was everywhere. Traders plied Native leaders with liquor even during negotiations. The liquor was so pervasive that observers doubted the integrity of the treaty process. Eyewitness Charles Jacob Latrobe later wrote, “Who will believe that any act, however formally executed by the chiefs, is valid, as long as it is known that whiskey was one of the parties to the treaty?”

The traders’ influence didn’t stop there. For decades, Native Americans had bought goods from them on credit, and the traders encouraged them to go further and further into debt. After years marked by strife, conflict, and economic difficulty, tribes owed more than they could afford to repay, especially because traders inflated both the prices and the size of the debt. These financial tactics were deliberate. In 1803, Thomas Jefferson wrote in a letter:

“We shall push our trading houses, and be glad to see the good and influential individuals among them run in debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop th[em off] by a cession of lands. …We shall thus get clear of this pest without giving offence [sic] or umbrage to the Indians.”

Once the tribes were pushed far enough into debt, Jefferson and others thought, they would have no choice but to sell their lands to pay what they owed. This tactic succeeded in the 1833 Treaty of Chicago. The treaty included a $175,000 payment directly to merchants the tribes owed. These were the same merchants who had supplied the whiskey and emphasized the size of the debt during the treaty negotiations.

Other details aren’t as clear. When negotiations started on September 14, Native leaders were firm that they didn’t want to sell their land. By September 26, terms had been established. Yet while the first week of discussion is relatively well documented, the record kept by government negotiators is blank for the five days before the 26th.

Some historians believe that this gap in the historical record indicates that the negotiators were doing something they didn’t want to document. Bribery is often suggested as a possibility since even politicians at the time thought financial fraud occurred.

George B. Porter, territorial governor of Michigan and one of the negotiators, was accused of using the treaty terms to funnel tens of thousands of dollars to his associates. Those associates were merchant families claiming the tribes owed them money. The U.S. Senate believed those claims were wildly inflated. Part of the treaty payment going to the Native Americans was also made in goods purchased from those same friends of Porter’s.

Whether or not there was financial corruption, the full payment likely wasn’t received by the tribes. Eyewitness Henry van der Bogart wrote, “The goods were deposited in two buildings and torn up into small pieces to be distributed and the avaricious French traders were permitted to watch them and stole to the amount of 20 thousand dollars worth in two nights.” He further accused the traders of stealing even more from drunk tribe members after the payment was distributed.

The 1833 Treaty of Chicago isn't unique—it's an example of how treaty negotiations with the Native Americans used lies, theft, and coercion. Once the terms of those treaties had been established, their interpretation would continue to have long-lasting consequences.

The Pokagon Potawatomi and the Chicago Coast

In October 1871, nearly 3.5 square miles of Chicago were destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire. When the city began to rebuild, the rubble had to go somewhere, and a lot of it went into Chicago’s favorite dumping ground: Lake Michigan.

Before the fire, the coastline of Lake Michigan was around where Michigan Avenue is now. The burnt trash extended the shoreline considerably into the lake bed. Neighborhoods like the Gold Coast and Streeterville, as well as Museum Campus and Lake Shore Drive, are all built on this landfill. But if the land was new—if it hadn’t existed before trash was pushed onto the shore—who owned it?

George Wellington Streeter, whose boat ran aground on a sandbar that was later connected to the shore by more rubble, is probably the most famous of the claimants (Streeterville is named after him). He argued that since the land was outside the boundaries of existing maps of Chicago and Illinois, it lay outside those jurisdictions. His fight with real estate developers for the rights to the land lasted decades, in and out of court. News coverage of his dispute varied, but it often praised his pioneering spirit.

The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi began to assert their right to the land in the late 1800s, but it wasn’t until 1914 that they found a lawyer, Jacob Grossberg of Chicago law firm Burkhalter and Grossberg, to sue on their behalf. The case, Williams v. City of Chicago, was appealed to the Supreme Court in December 1916.

The Potawatomi argued that previous treaties had ceded only specific areas of land that were defined in those treaties—and that unceded land still belonged to Indigenous groups. The land that Chicago now rests on had been surrendered by a group of tribes (including the Potawatomi) in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, but that land didn’t include the new lakefront. The Potawatomi had also never relinquished the rights to the lake bed that the new land rested on, or even the lake itself.

Newspapers of the time were much less favorable to the Potawatomi than to Streeter, with coverage dismissing their claim and often using racist stereotypes. “Cash or the Tomahawk: Red Men Prepare to Collect a Bill in Chicago,” reads a 1901 Chicago Tribune headline. The Supreme Court was more polite, but they ultimately dismissed the claim as well. In their 1917 decision, they argued that the tribes never had true ownership of any land in the Americas. If a tribe retained land after a treaty, they didn’t own it outright, they simply kept a right to occupy it. According to the Supreme Court, that right to occupancy had been abandoned when the Potawatomi left the land—even though the land itself had been under the lake.

This lawsuit set a precedent for other legal disputes regarding Native land rights. For an extensive look at the case, including the background and fallout, see Imprints: The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians and the City of Chicago.

Chief Shab-eh-nay and DeKalb County

The United States made many treaties with Native tribes but often broke the terms later. In 1829, the Treaty of Prairie du Chien reserved more than 1,280 acres in Illinois for Chief Shab-eh-nay of the Prairie Band of Potawatomi and his descendants. No later treaty (including the 1833 Treaty of Chicago) ever changed that. That land, which is in what is now southern DeKalb County, remained the legal property of Chief Shab-eh-nay.

Due to other treaties, much of the Potawatomi tribe eventually moved to Kansas, and in 1849, Chief Shab-eh-nay visited them. At the time, the only way to travel long distances was on horseback, and the journey to Kansas would have taken weeks. Despite the geographical realities of the trip, the United States government determined that the length of the chief’s visit meant he had abandoned the land, and they auctioned it off.

Unlike the Chicago lakefront decision from the Supreme Court in 1917, the federal government has since agreed that the Potawatomi are the legal landowners. In 2001, the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) wrote, “after considerable review of the relevant facts, we have determined that the Prairie Band has a credible claim for unextinguished Indian title to this land.” Despite the determination, in the 175 years since the reservation was seized and sold by the United States, the Potawatomi have never received reparations or the return of their reservation.

But things do change. Our March 2023 blog post about Indigenous Chicagoland noted that there was no federally recognized tribal land in Illinois. That’s no longer true. The Prairie Band of Potawatomi has spent 15 years and almost $10 million buying back just 130 acres of the 1,280 to which the DOI said they had a credible claim. In 2024, the DOI placed that purchased land in trust for them, officially making it an Indian reservation and affirming tribal sovereignty over that area.

The legacy of treaties and land ownership in Illinois is ongoing. In 2023, a bill (HB4107) was introduced to the Illinois House of Representatives. If it passes, it would return the 1,500 acres of Shabbona Lake State Park in DeKalb County to the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation and the descendants of Chief Shab-eh-nay. Depending on the outcome of that bill, it’s possible that we may report that things have changed again.