Telling the Story of Irene Higginbotham

February 7, 2025

By Christy Bennett, Musician

History is a funny thing. We are taught to trust the narratives we learn in school. We are taught that the words in our history books contain the whole story. But narratives are controlled by the hands that compose them. History books are limited by the perspectives that were given the power to write them.

Several years ago, I came across a 1939 article from the Detroit Free Press titled, "The Girls." It discussed a few of the women who had broken into Tin Pan Alley: Ann Ronell, Dana Suesse, and Kay Swift (notably, three white women). I realized we've been talking about women in jazz the same way since 1939. Very little has changed. Not much was written about them while they were working. Not much is left from which to reconstruct their stories. As a result, the same few facts are repeated, and short compilation stories are shared to include the "history of women in jazz."

The women who chipped away at the glass ceiling of the music world were resilient, brilliant forces of nature. Their stories deserve more than a quick mention in a women's history article. The details of their lives warrant uncovering, and the breadth of their musical contributions deserves to be revealed.

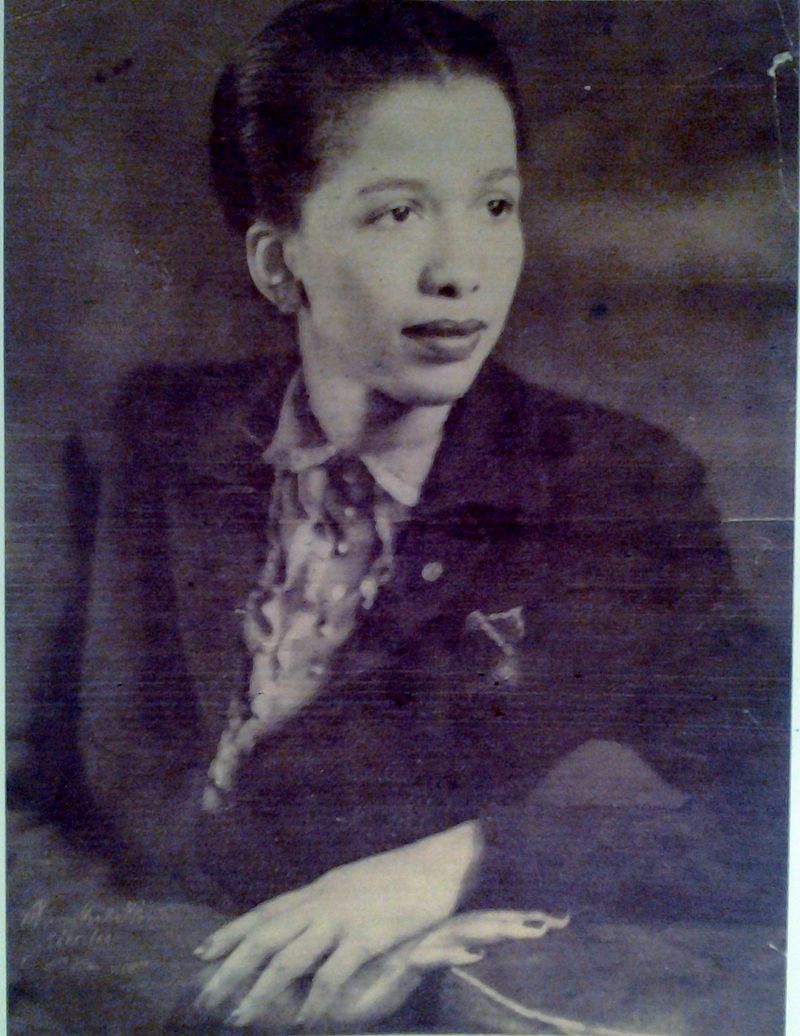

Irene Higginbotham was a songwriter who broke into the boys' club of songwriting. Billie Holiday, Tony Bennett, Nat "King" Cole (with whom she cowrote "I've Got to Change My Ways"), Anita O'Day, Coleman Hawkins, and many more giants of jazz performed her music. She was prolific, versatile, gifted, and unique.

Early Successes

Evidence of Irene's ambition and drive can be found in the years after she moved to New York City. When she was only 19 years old, musician and composer W. C. Handy included Irene's name in a dictionary of Black songwriters and musicians in 1937. She joined a group formed to advance Black songwriters by getting their music performed by the well-known bandleaders of the day. Several articles from the Pittsburgh Courier identify her not only as a founding member (the youngest in the group by 20 years) but also as the person who suggested the name for the group: Negro Songwriters' Protective Association.

The first recording of one of her songs was by Louis Armstrong in 1939. Her uncle, J. C. Higginbotham, played trombone in the group and Irene asked him to bring "Harlem Stomp" to a rehearsal. The group liked the tune so much that they included it in their next broadcast from the Cotton Club.

Irene's father, Garnet Higginbotham, wrote for the Atlanta Daily World. Between his influence and the insight from her uncle J. C., she understood the importance of publicizing your accomplishments. She got several short mentions of her success with "Harlem Stomp" in the East Coast Black papers and in her hometown of Atlanta.

Irene was a social butterfly, going out regularly to shows, rubbing elbows with musicians, and getting her tunes in as many hands as possible. She wrote music for race record albums and cranked out novelty tunes to support herself. She also became known on the scene as a skilled pianist and transcriptionist. She arranged the piano parts for Sammy Price's Boogie Woogie folio.

Overlooked in the Industry

Despite Irene's many accomplishments, her career failed to take off. Her successful songs did not result in getting more requests for compositions. The only musical she was offered to compose for was a production of Irvine C. Miller's Brown Skin Models in 1944, almost 20 years after the first version of the show. When Billie Holiday recorded "Good Morning Heartache," lyricist Ervin Drake was asked to join the musicians in the studio, but Irene was not. Her talent and connections in New York's music scene were limited to other Black artists, and the path to mainstream success was impeded.

Years after her passing, her song "Good Morning Heartache" remained a part of the Great American Songbook. While the song lived on, few knew her name. An article in 1982 from The New York Times discussing a Women's Jazz Festival mentioned the song and laid the groundwork for her name to be further erased from history books. In the article, her story is conflated with songwriter Irene Kitchings.

The mistake would be repeated many times in the years to follow. Two biographies from major publishers about Billie Holiday conflated Higginbotham and Kitchings. A Decca box set of Billie Holiday recordings melds the stories of the two women. Radio shows on Indiana Public Media discuss the "mystery of the two Irenes." By merging the two women, their contributions and accomplishments lose all connection to the women that earned them.

Uncovering her Legacy

Delving into the history of a Black woman like Irene Higginbotham has revealed the many ways modern-day history writers have continued the tradition of omitting them from the record. The only written records of Irene's career come exclusively from Black papers like the Atlanta Daily World, the Chicago Defender, and New Amsterdam News. Most of the reviews she received in Metronome Magazine primarily came from songs that would have been labeled "race records." Details of her geographic location can only be found in passing references from her father's columns for the Atlanta Daily World.

The newspapers never interviewed her for a fluff piece, as they did with a few of her white female counterparts. When the major motion picture Lady Sings the Blues revitalized interest in Billie Holiday and the tune "Good Morning Heartache," no one looked up the woman who was asked to write the famous song. When she passed away in 1988, the New Amsterdam News was the only newspaper that published a very short obituary. Compare that to the large spread with photographs of Ervin Drake, one of her male coauthors, in The New York Times and the Washington Post.

Irene Higginbotham had to work harder, hustle tenaciously, and be more talented than her white male counterparts to achieve a sliver of success in the music industry. She deserved more opportunities while she was alive. She deserves to have her story told and her contributions remembered.

Note from the library: Christy will be performing music by Irene Higginbotham in the library auditorium at 3 pm on Sunday, March 16. Free tickets will be given out to those present beginning at 2:30 pm.