Asian Americans in Skokie–A Tale of Changing Demographics and Attitudes

May 3, 2022

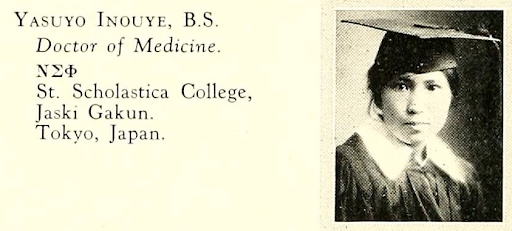

In 1930, Yasuyo Inouye lived on Simpson Street in what was then Niles Center--now Skokie. Dr. Inouye, who received her MD degree in January 1930, entered the United States in 1921. She attended St. Scholastica College in Duluth, Minnesota, before attending Loyola, and she then served an internship at St. Francis Hospital. In 1931, she returned to Japan, where she worked with the Anti-Tuberculosis Association.

Dr. Inouye only spent a short time in Skokie. She was not only remarkable for being one of a small number of women studying medicine at the time, she was unique to Skokie as well. In 1930, she was the community’s only Asian resident.

Things have changed. According to 2020 census information, Skokie is about 55% white and 27% Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI), the second largest racial group in Skokie, and those numbers reflect a relatively recent demographic shift. In the 1970 census, Skokie’s population was 99% white. By 1980, 7% of Skokie’s population was Asian American, as Asian residents of Chicago began moving to the suburbs in search of higher property values and better schooling for their children. In 1990, the AAPI percentage had increased to 15%, and by 2000, AAPI community members were 21% of Skokie’s total population.

Census data is just one way to understand the history of Asians and Asian Americans in Skokie. Local news coverage can show prevailing attitudes of our community’s majority—both good and bad. While most early articles about Skokie’s growing AAPI population are positive, the way in which they’re positive tells us about our historical biases and stereotypes.

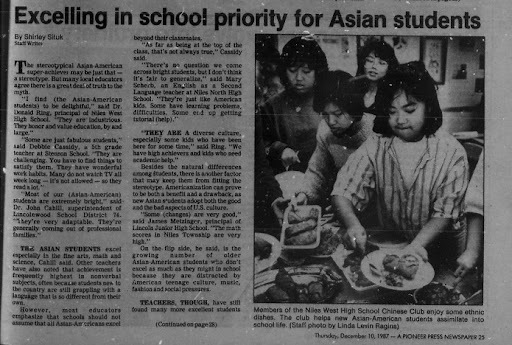

A Chicago Tribune article from 1985 reassures readers that property values won’t decrease as a result of the demographic shift. Like many other newspaper articles from that time, it points out that new AAPI residents of Skokie were usually educated professionals. Pages in the Skokie Review and Skokie Life focused on how well Asian American students did in school. While on the surface these articles are complimentary toward AAPI community members, they also—sometimes explicitly—draw comparisons to other minority groups, revealing a less positive attitude toward immigrant communities as a whole. Such complimentary coverage also feeds into the model minority myth, an oft-repeated historic bias that Asian Americans are inherently polite, submissive, hardworking, and academically successful. While it may seem counterintuitive to characterize a stereotype as negative when it calls a group successful, the model minority myth homogenizes the AAPI experience, whitewashes a history of anti-Asian bias, and denies AAPI students and adults appropriate support when their teachers and peers make assumptions about their needs.

Skokie’s local newspapers, specifically, were historically positive about the village’s new residents. Articles with more varied geographical coverage had different opinions, like the Chicago Sun-Times, which suggested (inaccurately) in 1999 that white families had become the true minority in Skokie. Local papers were, by contrast, almost celebratory about the growing diversity in the village. However, that celebration came with its own downsides.

While journalists, government officials, and teachers in the historical record all expressed a desire to help immigrant families, that “help” usually meant “assimilation.” In addition to describing growing AAPI communities as hardworking, polite, and educated, by and large, the newspapers agreed on one more descriptor: isolated. Historical newspaper coverage does show that leaders in Skokie wanted to change that sense of isolation and segregation. On the surface, addressing these issues within the community is positive. In practice, however, the reported efforts prioritized assimilation: “The process of Americanization happens quickly,” the Skokie Review quotes then-Mayor Albert J. Smith in 1987.

Assimilation isn’t always the opportunity immigrant communities are looking for—it is not the same as inclusion or mutual cultural exchange. Since 1969, Skokie has been home to the Chinese Cultural and Educational Association (CCEA), the oldest Chinese language school in the area outside Chinatown. CCEA has the stated goal of disseminating Chinese culture not only to the local Chinese community but to everyone, of any cultural background. Yet when Skokie news coverage in the 20th century talked about how to connect with AAPI families, they talked about assimilating those families into American culture—not encouraging community members to take a class about Chinese culture, for example.

Another common narrative throughout the historical newspaper coverage is that AAPI families moved to Skokie because the village created such an inclusive environment—both Skokie’s Fair Housing ordinance and the community response to the attempted Nazi marches in the 1970s are cited as examples that everyone was welcome here. When we compare those pronouncements of welcome with contemporary community demographics, however, we see that no other racial groups were moving to Skokie in the same numbers at the time. (This difference has held true since. In the 2020 census, while AAPI residents made up 27% of the population, the next two largest demographic groups, Black and Latinx residents, were 10% each.)

The reality of inclusion is more complicated, despite the clear pride in reports of village efforts to aid in assimilation. In December 2000, Skokie held a Peace and Harmony rally in response to a Klan demonstration. The event took place not long after a series of violent attacks on Asian women earlier that year and the 1999 hate crime that injured 10 people and left 2 dead, including Skokie resident and Northwestern University men’s basketball coach Ricky Byrdsong. Not half a year following the rally that celebrated Skokie’s diversity, candidates for local office who had Asian names performed significantly worse in the local election than opponents with Western names. Our historical record shows evidence that proclamations of unity are not the same as active inclusion throughout the community.

Our local history, and the history of bias and violence against AAPI individuals, is especially worth reflecting on now, considering both the recent anti-Asian sentiment during the COVID-19 pandemic and the passage of the TEAACH Act, requiring that all public school students in Illinois learn Asian American history as part of the school curriculum. With a demographically diverse community, continued focus primarily on assimilation disregards the knowledge and lives of our neighbors.

There are many opportunities to learn and to find joy in new experiences—at local organizations like CCEA, at Chicago-based organizations like the Japanese-American Service Committee and the National Cambodian Heritage Museum, and at the library itself, throughout the year. In Skokie, we can be proud of our past, and we can learn from it to be proud of our growth and, with hope, our future.